MoMA Blog

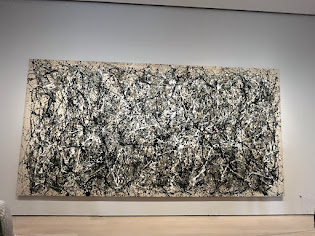

Jackson Pollock, one: Number 31,1950, Oil and enamel paint on canvas, 8' 10" x 17' 5 5/8" (269.5 x 530.8 cm

Joan Mitchell, Ladybug,1957, Oil on canvas, 6' 5 7/8" x 9' (197.9 x 274 cm)

In 1957, the year in which she made Ladybug, Mitchell said of her process, “The freedom in my work is quite controlled.” She meticulously applied each color, attentive to the relationships between them and to the weight of each brushstroke. In this painting and others of this period, Mitchell, unlike many of her Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, rejected an allover compositional approach, preferring a balance of figure and ground—even in a fully abstract image. Throughout her long career, Mitchell referred to the matter of her paintings as “feelings,” or memories of distinct times and places, the uneven flow of which she fixed in paint. Mitchell was thirty-two and living in New York when she painted Ladybug. Here, as in her other works, she aimed not to describe nature, but (as she put it) “to paint what it leaves me with.” " https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79586

" Robert Rauschenberg is widely regarded as a predecessor of the Pop artists, because of his incorporation of the stuff of everyday life including anything that caught his imagination, from rubber tires to light bulbs into his wide-ranging work. In many of his works, like Bed, he merged elements of postwar abstract painting with found objects.Bed is one of Rauschenberg’s first combines, a term he coined to describe the works resulting from his technique of attaching found objects to a traditional canvas support. In this work, however, there is no canvas. The artist took a well-worn pillow, sheet, and quilt, scribbled on them with pencil, splashed them with paint in a style similar to Jackson Pollock’s action paintings, and hung the entire ensemble on the wall.The story goes that Rauschenberg used his own bedding to make Bed, because he could not afford to buy a new canvas. “It was very simply put together, because I actually had nothing to paint on,” he reflected years later, in 2006. “Except it was summertime, it was hot, so I didn’t need the quilt. So the quilt was, I thought, abstracted. But it wasn’t abstracted enough, so that no matter what I did to it, it kept saying, ‘I’m a bed.’ So, finally I gave in and I gave it a pillow.” Hung on the wall like a traditional painting, his bed becomes a sort of intimate self-portrait consistent with his assertion that “painting relates to both art and life…I try to act in that gap between the two.” " https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/robert-rauschenberg-bed-1955/

The story goes that Rauschenberg used his own bedding to make Bed, because he could not afford to buy a new canvas. “It was very simply put together, because I actually had nothing to paint on,” he reflected years later, in 2006. “Except it was summertime, it was hot, so I didn’t need the quilt. So the quilt was, I thought, abstracted. But it wasn’t abstracted enough, so that no matter what I did to it, it kept saying, ‘I’m a bed.’ So, finally I gave in and I gave it a pillow.” Hung on the wall like a traditional painting, his bed becomes a sort of intimate self-portrait consistent with his assertion that “painting relates to both art and life…I try to act in that gap between the two.” " https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/robert-rauschenberg-bed-1955/

Claude Monet, Water Lilies,1914-26, Oil on canvas, three panels, Each 6' 6 3/4" x 13' 11 1/4" (200 x 424.8 cm),overall 6' 6 3/4" x 41' 10 3/8" (200 x 1276 cm "In the final decades of his life, Monet embarked on a series of monumental compositions depicting the lush lily ponds in his gardens in Giverny, in northwestern France. At the end of the nineteenth century, the painter had envisioned a circular installation of vast paintings—he called them *grandes décorations*—that would envelop the viewer in an expanse of water, flora, and sky. This vision materialized in the form of some forty large-scale panels, Water Lilies among them, that Monet produced and continuously reworked from 1914 until his death in 1926.

At this triptych’s center, lilies bloom in a luminous pool of green and blue that is frothed with lavender-tinged reflections of clouds. Thick strokes in darker shades seep into the left panel, while on the right, sky and water are gently swallowed by an expanse of reddish-green vegetation. The dense composition hovers at the threshold of abstraction, its lack of horizon creating an effect of total immersion. After Monet’s death, twenty-two panels were installed on curved walls in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris: a gift from the artist to the nation of France. The remaining canvases stayed in his studios until the late 1940s, when collectors and MoMA curators began to take an interest in them." https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80220

At this triptych’s center, lilies bloom in a luminous pool of green and blue that is frothed with lavender-tinged reflections of clouds. Thick strokes in darker shades seep into the left panel, while on the right, sky and water are gently swallowed by an expanse of reddish-green vegetation. The dense composition hovers at the threshold of abstraction, its lack of horizon creating an effect of total immersion. After Monet’s death, twenty-two panels were installed on curved walls in the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris: a gift from the artist to the nation of France. The remaining canvases stayed in his studios until the late 1940s, when collectors and MoMA curators began to take an interest in them." https://www.moma.org/collection/works/80220

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night, Saint Rémy, June 1889, Oil on canvas, (73.7 x 92.1 cm)

"In creating this image of the night sky dominated by the bright moon at right and Venus at center left van Gogh heralded modern painting’s new embrace of mood, expression, symbol, and sentiment. Inspired by the view from his window at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy, in southern France, where the artist spent twelve months in 1889–90 seeking reprieve from his mental illnesses, The Starry Night (made in mid-June) is both an exercise in observation and a clear departure from it. The vision took place at night, yet the painting, among hundreds of artworks van Gogh made that year, was created in several sessions during the day, under entirely different atmospheric conditions. The picturesque village nestled below the hills was based on other views it could not be seen from his window and the cypress at left appears much closer than it was. And although certain features of the sky have been reconstructed as observed, the artist altered celestial shapes and added a sense of glow.

Van Gogh assigned an emotional language to night and nature that took them far from their actual appearances. Dominated by vivid blues and yellows applied with gestural verve and immediacy, The Starry Night also demonstrates how inseparable van Gogh’s vision was from the new procedures of painting he had devised, in which color and paint describe a world outside the artwork even as they telegraph their own status as, merely, color and paint." https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79802

Van Gogh assigned an emotional language to night and nature that took them far from their actual appearances. Dominated by vivid blues and yellows applied with gestural verve and immediacy, The Starry Night also demonstrates how inseparable van Gogh’s vision was from the new procedures of painting he had devised, in which color and paint describe a world outside the artwork even as they telegraph their own status as, merely, color and paint." https://www.moma.org/collection/works/79802

Comments

Post a Comment